Beyond the Surface: Uncovering Canada's Hidden Drug Crisis

Canada's drug laws hinder rights, harm marginalized communities, and erodes the country's democratic obligations. Decriminalization offers a proven path for reform.

By Vivian Allison

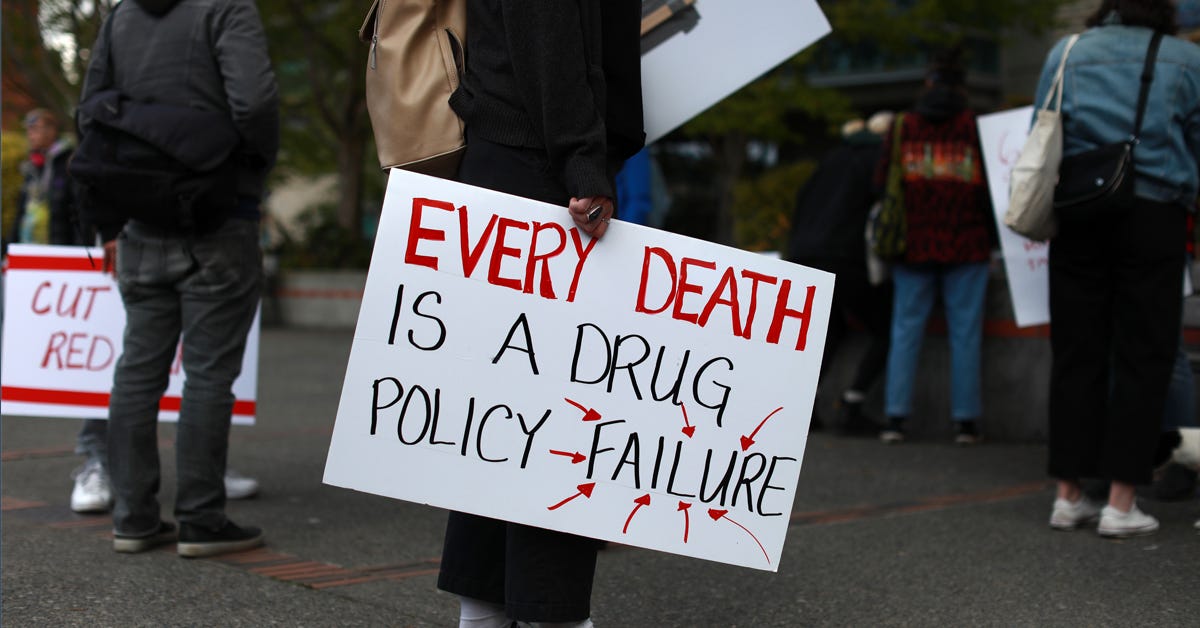

CANADA HAS A DRUG PROBLEM – but not just in the way that it is often talked about. Criminalizing the possession of drugs for personal use, as outlined in the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, not only fails to achieve its targets but also obstructs individuals from the full realization of their fundamental rights and freedoms.

Confronting mental illness as a criminal offense deepens systemic inequality and discrimination, impedes access to adequate healthcare, and excludes individuals from having a meaningful place in society. Therefore, an overarching question arises: Are existing drug laws eroding Canada’s democratic vision?

Canada’s War on Drugs (WOD) has had well-documented detrimental effects, disproportionately impacting racialized communities. Although "tough-on-crime" laws were initially intended to target high-level drug traffickers, a staggering 62 percent of arrests targeted low-level cannabis. An alarming 75 percent of these arrests were related to possession charges.

The policing of these laws, moreover, overly focused on vulnerable communities with higher levels of poverty and unemployment, resulting in the targeting of racialized communities – especially Black Canadians and Indigenous peoples. The result has been intensifying structural violence against marginalized groups, and the WOD continues to have devastating impacts on racialized communities even a decade later.

Despite representing only 4 percent of the adult population in Canada, for example, Black Canadians represented 9 percent of offenders under federal jurisdiction from 2020 to 2021, creating a damaging and pervasive association between Blackness and criminality. Similarly, 28 percent of inmates in federal institutions were Indigenous from 2017 to 18 despite representing only 4.1 percent of the population.

The injustices faced by Indigenous peoples are further compounded by ongoing traumas from colonization, including the lasting psychological impacts of residential schools, high levels of poverty and child abuse, and the abysmal quality of public services that have made them more vulnerable to drug-related harms. For both Black Canadians and Indigenous peoples, disproportionate incarceration has spawned a self-perpetuating cycle of drug use, incarceration, racial stigmatization, mental health issues, and poverty that continues to this day.

One would hope at the very least that these devastating policies would achieve their goal: to disincentivize the use of illegal substances and reduce the harms associated with drug use. However, they have failed on both accounts as the WOD has engendered an epidemic of drug overdoses and a nefarious, yet lucrative, black market.

Quality control in this illegal market goes unchecked, leading to more lethal substances that make the odds of overdose exponentially higher. Despite these very real concerns, the continued criminalization of personal possession drives drug use underground instead of toward safer means of consumption. This, in turn, exacerbates the transmission of HIV, Hepatitis C, Hepatitis B, and other fatal infections as individuals resort to riskier drug injection methods.

Not only is disease spreading but so are opioid-related deaths, with approximately 20 Canadians dying each day between January and September of last year from opioid overdoses. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, social stigma underlies why only 18 percent of people with drug-use disorders receive adequate care and treatment.

Moreover, the fear of being charged with criminal offenses further impedes individuals from seeking the very healthcare services that are crucial in mitigating some of the most harmful consequences of drug use and bringing users on the path toward recovery. This punitive approach to drugs that incarcerates rather than helps people is one of the reasons why roughly half of prison inmates have a substance use disorder. To make matters worse, these Canadians have not only been stripped of their freedoms but also lack any real form of treatment, often leading to recidivism, relapse, and overdose upon release.

Canada’s municipalities and provinces are beginning to demand change. Edmonton, Vancouver, and Toronto have requested that the federal government decriminalize small amounts of substances such as cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl. Meanwhile, a Supreme Court of British Columbia decision granted a section 56 exemption of the CDSA to Insite, a supervised injection site, allowing it to administer healthcare services to drug users to curb the opioid crisis in Vancouver.

This litigation demonstrates the clear contention between Canada’s drug laws and healthcare services. Even more than that, these recent developments show how drug laws are obstructing Canadians from realizing their equal right to life upheld by the Charter of Rights and Freedoms by making it almost impossible for individuals with drug-use disorders to get the help they need.

Canada clearly needs to reform its drug policy – and, luckily, there is already a successful case of drug policy reform that Canada can draw upon. In Portugal, all drugs were decriminalized in 2001. Since then, drug-related deaths have significantly declined in Portugal, whereas the average in the EU where drugs are still criminalized to various degrees has increased. Furthermore, the proportion of prison sentences in Portugal has fallen from 40 percent to 15 percent between 2001 and 2015, freeing the judicial system to re-allocate its scarce resources to other matters.

Drug-related transmitted diseases have also declined, with a decrease in ‘high-risk’ opioid use overall. This sharply contradicts the common narrative that decriminalization will encourage drug use and damage the well-being of local communities, instead demonstrating that decriminalization can be a force, not for evil, but for good.

It is now Canada’s turn to take a more humane and evidence-based approach to drug policy that allows all Canadians to thrive. The ball is in the Government’s court – and Canadians are watching.

Vivian Allison is a Master of Public Policy candidate with the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. With a background in Environmental Engineering and Math Education, Vivian has long been driven to implement her analytical and evidence-based thinking to create effective climate policy. Given the complexity of the climate issue, Vivian’s passions range across many social dimensions and global patterns of inequality.

Excellent analysis Vivian. Very much enjoyed reading this informative and entertaining article.