Expertise Under Attack: COVID-19’s Role in the Polarization of American Politics

The pandemic has perpetuated a cycle of ruthless cynicism against the civil service, compromising its fundamental legitimacy. Does this signal the demise of an apolitical bureaucracy?

By Jack Burnham

While the World Health Organization recently lifted its declaration of a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern” for COVID-19, the legacy of the pandemic remains readily apparent across much of public life. As Washington raced to combat the emergency and exercised unprecedented authority within a highly charged political climate, the actions of government officials radically challenged long-standing norms over the role of a professional, apolitical civil service within American democracy.

From scientific journals to schoolhouses, the partisanship produced by the pandemic has provoked a reckoning over the importance of impartial expertise within an increasingly polarized society in which opinions have become the primary fodder of public discourse. The pandemic has not only redefined the importance of the administrative state in the modern era, but it has also created a long-lasting distrust in the essential roles of government and increased polarization by promoting deep skepticism towards an impartial, fact-based public service.

The history of the civil service in the United States has long been marked by the combination of expertise and apoliticism. Emerging largely out of the Progressive Era, the modern civil service system was designed to promote expertise and professionalism through a rigorous meritocracy and a reliance on well-trained public servants.

From the founding of NASA to the expansion of the National Institutes of Health, the federal government invested in sustaining technical excellence and innovation both as an economic and military necessity, and as a symbol of American prestige. Further, aside from funding these public institutions, administrations of both parties routinely sought to protect them from partisan malfeasance, from eliminating the well-entrenched spoils system to adopting standardized testing as a requirement to enter government.

The crisis of the pandemic promptly shattered this ethos of expertise and apoliticism as a novel, swiftly moving respiratory virus forced the government to stage extraordinary interventions into the lives of a frightened, suspicious public. As public health experts joined elected officials on television screens across the nation, Americans’ belief in the value of expertise became a new division within politics, accelerating both the process of polarization and the public’s cynicism towards the civil service.

Rather than being able to rely on professional consensus supported by prominent elected officials from across the political spectrum, the pandemic prompted science to operate at near warp-speed, eroding the perceived value of expertise. As policymakers relied on preprints to determine sweeping regulations, governments were routinely forced to issue stark reversals on masks, vaccines, and business restrictions and release seemingly conflicting directives.

While these efforts were often necessary given the nature of the crisis, such revisions also bred public distrust, particularly as initial predictions regarding the intensity of the crisis proved false. Moreover, the demand for concepts that could be easily communicated across multiple platforms also limited scientists’ capability to introduce nuance into the public discourse, further constraining the value of expertise within a complex crisis.

The pandemic also forced scientists and other experts into the political sphere, whether directly as representatives of the executive, or indirectly as politicians cited their findings in their decision-making. Although this coordination allowed for the development of evidence-informed policies, it also inherently politicized a typically apolitical space, particularly as politicians and voters aligned themselves as “pro” or “anti” science. Rather than recognizing the limitations of the evidence, which were openly acknowledged by the scientific community, prominent Democrats demanded that the Trump administration “follow the science” while touting their own support of “scientific” policies such as school closures.

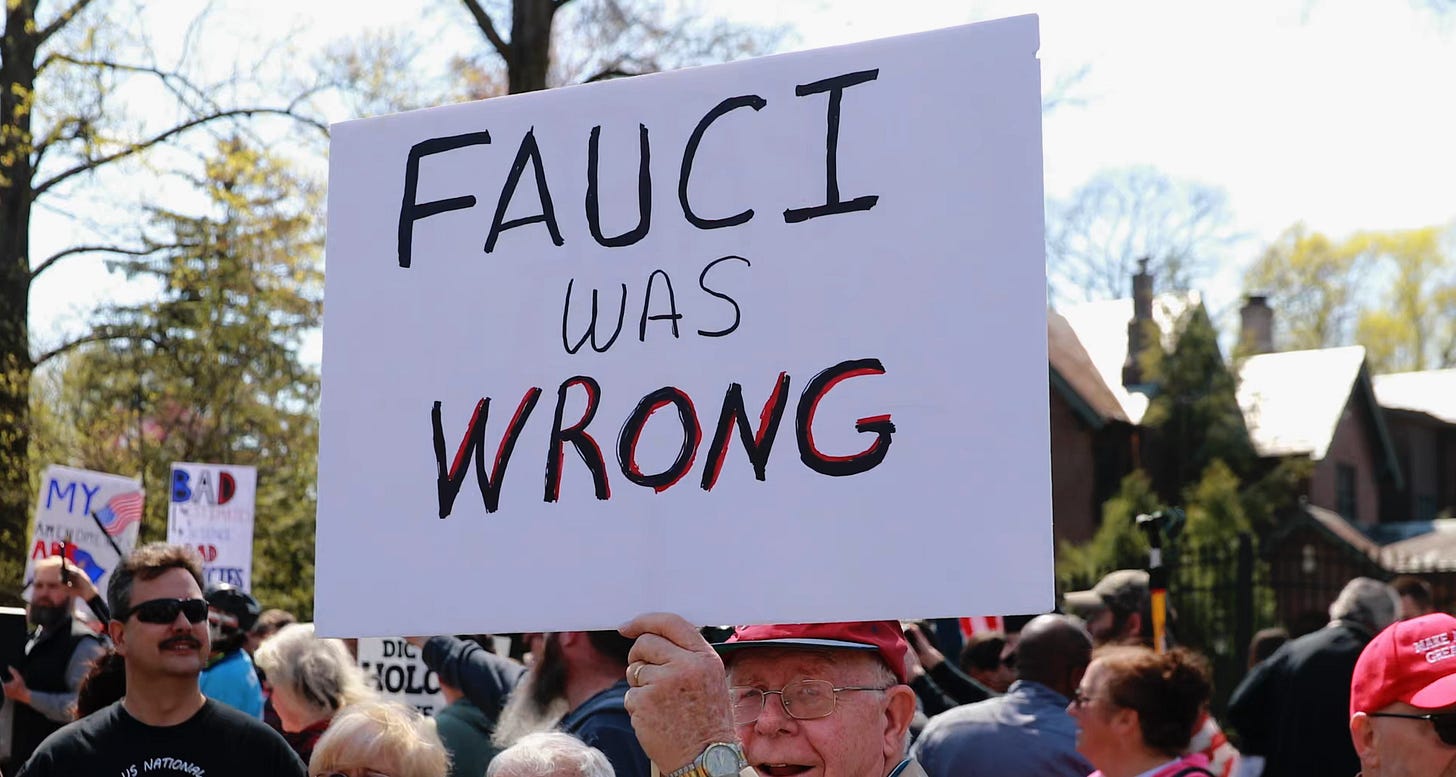

In response, Republican lawmakers openly mocked officials such as Dr. Anthony Fauci for appearing to wade into political controversies. However, this phenomenon was not only limited to the civil service, as prominent scientific journals such as Nature offered political endorsements during the 2020 election, further harming the public’s perception of the broader profession’s apoliticism.

While the barrier between expertise and politics has been effectively shattered by the pandemic, there is little guarantee that its retreat will allow this wall to reform. Rather than merely fostering suspicion of political leaders, the pandemic has also heightened Americans’ distrust in the fundamental competency of the civil service. From the classroom to the ballot box, Americans’ willingness to accept an administrative state guided by professional expertise has been upended by demands for parental rights, outrage over school closures, and accusations of fraud and election-rigging.

Rather than relying on traditionally apolitical sources of authority such as education officials, election experts, and prominent generals, the post-pandemic period has been marked by the injection of partisan politics into school board races, election monitoring, and military training. While partly representative of the salience of issues such as voting rights, national security, and curriculum development, these trends also highlight a growing distrust in government amongst an increasingly larger segment of the public, compromising its fundamental legitimacy.

Further, as evidenced by elections from Virginia to Florida, this phenomenon appears likely to continue as politicians seek to capitalize on the perceived partiality of experts to win office, perpetuating a cycle of ruthless cynicism against the civil service.

Even three years after the beginning of the crisis, the legacy of unprecedented government intervention, scientific uncertainty, and intense backlash continues to influence the tenor of partisan politics. The pandemic compelled the government to take a more active role in citizens' lives, which resulted in scientists and other experts becoming political figures in their own right. This, in turn, eroded public trust in the civil service's fundamental competence.

Rather than prompting Americans to develop an appreciation for the value of apolitical expertise, the crisis has contributed to the overt politicization of previously non-partisan realms of public life and heightened suspicion over the benefits of evidence-based policymaking. Despite the virus’s retreat from the headlines and hospital beds, the health of an apolitical civil service remains in terminal decline.

Jack Burnham is a Master of Public Policy candidate with the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He has an interest in international defense and security and hopes to continue with his research into power transitions within the international system and great power competition.