Lithium is the next oil

While essential to producing EVs, Burtynsky’s work shows us the environmental crisis unfolding behind the scenes.

By: Rebecca Kresta

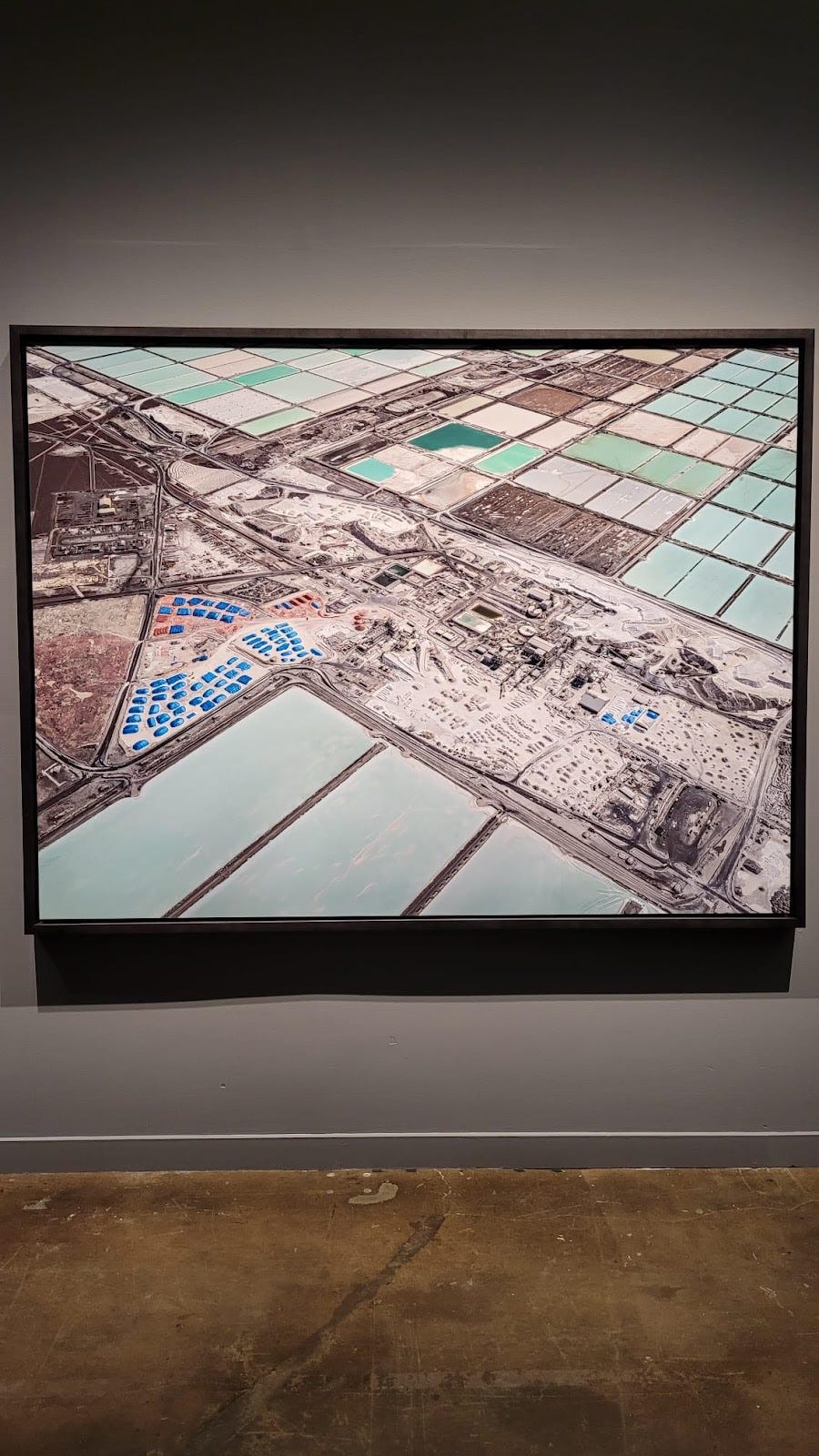

Blue spots against a background of white. Upon closer inspection the spots reveal themselves to be tarps and the white to be desert sand. We’re looking at a lithium mining plant in Chile. The abstract composition of Edward Burtynsky’s wall sized, esoteric landscapes draw us in. Burtynsky’s work, shown at the Arsenal Contemporary Art Contemporain in Montreal this past September, is beautiful, but his words exposing the complexity of the environmental crisis are striking. The plaque next to the photo gently explains that lithium is a highly explosive element that is mined for rechargeable batteries, two to four grams for a cell phone and eight to 12 kilograms in the average electric car.

Industry analysts predict that the number of electric vehicles (EVs) on the road will increase from 11 million to more than 145 in the next six years. While buyers give EV dealers rosy feelings about fighting climate change, there is still not enough conversation about the impact of lithium mining or treatment of dead batteries.

The uptake of electric vehicles has gained momentum both because the cost of vehicles has reduced and because government support has increased. California will officially ban the sale of all gas-powered vehicles by 2035. In Quebec, there is a rebate for up to $7000 for the purchase of an electric vehicle. The Canadian government has mandated that by 2035 all new vehicle sales must be electric.

Buyers are additionally incentivized by promises of lower maintenance and fuel costs, and anticipated positive emotions. A study in Psychology Today showed that positive anticipated emotion was more a prominent motivator among people intending to buy an electric car than negative anticipated emotion or moral norms.

McKinsey analysts and Elon Musk agree on at least one thing: lithium is the next oil. The lightest known metal on the planet, it is used in batteries for both electric vehicles, grid storage and consumer electronics. Following the increased demand for EVs, demand for lithium is projected to grow from 500,000 metric tons in 2021 to some four million metric tons in 2030.

The oil metaphor extends beyond an economic boom. Like oil, lithium is not found alone in nature; it must be extracted either from hard rock or from lithium brine. Hard rock extraction harms the soil and causes air contamination. Brine extraction requires long evaporation processes that consume a massive quantity of water: 1000 litres per 1 kilogram of lithium. Many places where lithium deposits are found (such as Chile, Argentina, and Australia) are water-scarce areas. Already, the presence of lithium mines has caused a water scarcity conflict in Chile.

Lithium mining for batteries, while harmful for the environment, still outperforms oil production. You don’t need to buy new car batteries every 100 kilometres, unlike refilling the tank of a gas-powered vehicle. Manufacturing a petrol or diesel car releases about seven to 10 tonnes of CO2. Making an electric car requires the same resources, plus an additional nine tonnes of CO2 to fabricate the batteries. However, if your energy source is renewable, then an electric vehicle produces less carbon emissions than a combustion vehicle over its life cycle.

The issue that Burtynsky exposes is that EVs are not a silver bullet solution with no impact. Scientists are already working on alternatives such as iron batteries. Iron is a more common mineral with much less dangerous extraction practices. There are also experiments on adding Tellurium to batteries which would extend their life by 400 percent.

Historically, only nine to 10 percent of lithium-ion batteries make it to appropriate recycling facilities. EV batteries are too large and too toxic to be ignored. The first wave of end-of-life EV batteries is expected to arrive in 2030, when an estimated 1.7 million tonnes of battery waste will need to be disposed of. This has led to a blooming battery recycling economy and improvements to technology. Traditionally, battery recycling is done through high temperature melting and an energy intensive process; however, new less-intensive technologies using hydrometallurgy are emerging.

Li-Cycle, a company based in Canada and the US will soon open a facility that allows them to recover up to 95% of car battery materials. Car manufacturers are supportive of battery recycling as they recognize that it will supplement their supply. But they are making life difficult for recyclers by using many different battery compositions and tough glues, which make the recycling process more complex. This is an area where policies could make a difference – by enforcing types of battery design that are easier to recycle, EV manufacturers could help ensure the long-term sustainability of their industry.

Burtynsky’s photographs capture not only the massive impact of extraction and manufacturing, but also the massive piles of battery waste produced, reminding us that as consumers, we are the drivers behind these images. Most people have accepted that climate change is real and that we must act. EVs are a positive development which allow us to move away from using fossil fuels, but we must avoid solving one resource crisis with another.

The government has a responsibility to incentivize not only the purchase of green technology, but to ensure that technology will be sustainable in the long run. And as consumers, we have a responsibility to remain critical of the environmental practices that we support – while more EVs on the road is a welcomed step to reducing our emissions, it is certainly not a long-term solution. Consumers and decision-makers alike must work to address the environmental impacts of lithium mining, while also devising new ways to meet our climate change obligations.

Rebecca recently returned from South Sudan where she was working in a remote area to build a large medical clinic. Prior to working for Médecins Sans Frontiers she was running an 80-person operations team manufacturing commercial engine parts for GE Aviation in the Eastern Townships. Rebecca is passionate about international development and has witnessed the importance of infrastructure in allowing communities to flourish. She wants to learn how public policy can be used to answer the questions that challenge our generation.

It certainly is important to address that "EVs are not a silver bullet solution with no impact". Better alternatives do not mean perfect alternatives, and this should always be taken into account during the public policy cycle