Stairway to Heaven: The BC NDP's 'One Neat Trick' for the Housing Supply Crisis

As housing prices soar nationwide, BC’s promising single-stair experiment is at risk.

By Jacob Kates Rose

In August, the British Columbia government took a meaningful but under-reported step towards addressing the housing crisis by becoming the first Canadian jurisdiction outside of Montreal to allow for apartment buildings up to six storeys with only one exit staircase. Single egress-stair designs (SES), ideally combined with reformed zoning laws surrounding height, unit density and lot coverage should catalyse the construction of the missing-middle housing that Vancouver, Victoria and the lower mainland so desperately need to combat soaring housing prices.

Why does such a small change have the potential to make a transformative impact? Because at its core, housing affordability is about supply and demand. When the demand for housing in a certain area exceeds the supply, units go to potential tenants and owners willing to pay the most. Everyone else is priced out of their desired area and pushed to less desirable neighbourhoods – or even other provinces. Just ask all the Torontonians calling Halifax home, or recent Vancouver-to-Calgary transplants.

Demand is up for a variety of reasons: more people live longer alone before starting families. Canadians also live longer, welcome more newcomers, and expect more in the way of living space, to say nothing of the centralisation of Canada’s economy in its largest cities.

Supply is down for a variety of reasons as well. Mostly, Canada is not building as many homes as it used to, and those homes we do build tend to accommodate fewer people. Gone are the strawberry box three and four bedrooms and here are the 300 square foot labyrinthine one bedroom condos. Part of the bottleneck in supply is urban and suburban zoning laws and building codes which make it harder (read: either illegal, more expensive, or both) to construct multi-unit housing in most of Canada’s urban areas.

Governments at every level are exploring strategies to shift these supply and demand curves. In past years, the federal government announced the First Home Savings Account and a seven year hiatus on GST collection from purpose built rental projects nationwide. Provinces and municipalities, who often share jurisdiction over zoning laws and building codes, are exploring on the ground solutions. BC’s single-stair egress is one such strategy.

Why does eliminating one measly staircase impact the construction of multi-unit apartments? Simply put, it makes it cheaper to build better units on more lots across a given city, especially three and four bedroom units, by improving the floor plan, the lighting, the ventilation, and – crucially – the economics of multi-unit apartment projects.

In most of Canada (except for Montreal) provincial building codes require buildings above three storeys have two interior egress staircases. This leads to double-loaded corridors, a technical term for a floorplan with units placed on both sides of a long central hallway that terminates in exit stairs at both ends. Units occupy the space between the central hallway and the exterior wall. Windows – and therefore bedrooms – can only be placed on one side of a unit, so adding a third or fourth bedroom to a double-loaded hallway floorplan requires stretching the unit further down the building’s exterior. This creates a long interior hallway within the unit, running parallel to the building’s shared hallway. Windows on one side of the unit also mean that, apart from coveted corner units, no resident gets a cross breeze, and north-facing occupants don’t get direct sunlight. This drives up the need for air conditioning and lighting, increasing the building’s energy demand.

Because of the high proportion of unrentable space consumed by interior hallways in three and four bedroom units in jurisdictions requiring double egress, only large developments full of one-bedroom units are financially viable for housing suppliers to construct. The large format flats that make Barcelona, New York, Montreal and the historic downtowns of many North American cities so desirableare economically unviable to build today due to the double egress requirements, and illegal to build with the preferable single egress model due to North American building code standards.

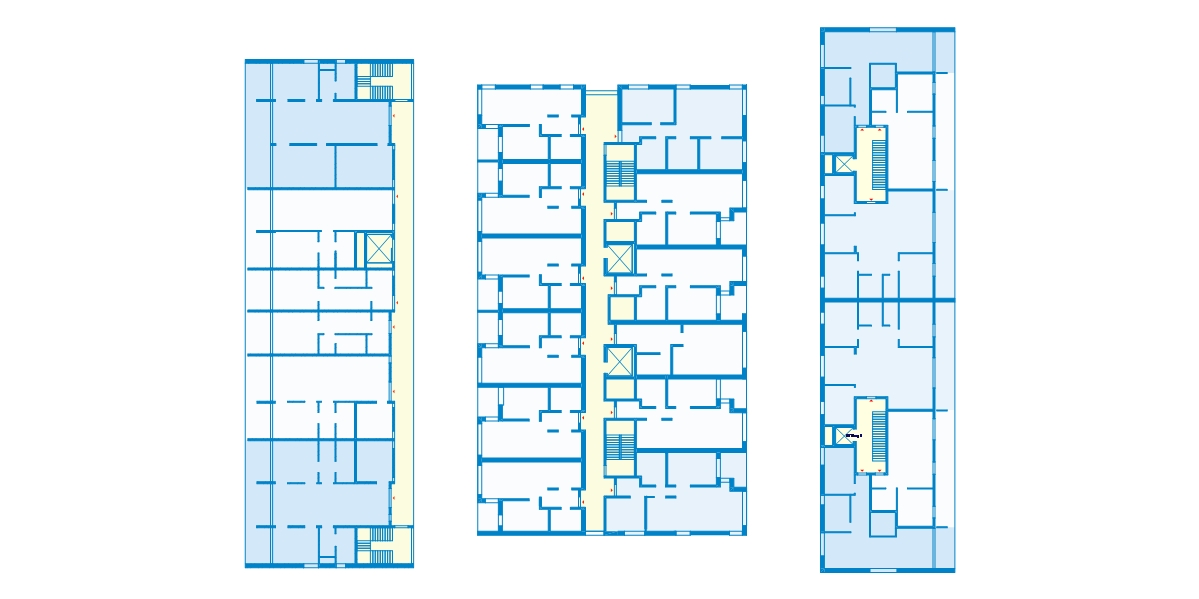

Most of Europe’s great cities, as well as New York and Montreal do not feature a double egress requirement. Rather they allow for a point access model where unit doors are accessed directly from landings. Consider the floor plans below, courtesy of the architect and single-stair zealot Michael Ellison.

The rightmost floor plan features much less wasted hallway space. Of its six units, four of them touch two or more exterior walls, reducing the need for air conditioning to control the temperature and providing natural light throughout the day. Without as much unrentable space and with the freedom to wrap around the building, developers can tap into the market for larger formats with three and four bedrooms. Housing providers can also situate projects on smaller lots where the second stair requirement isn’t just economically but spatially prohibitive.

However, we shouldn’t confuse one solution for a panacea. BC firefighting officials have raised concerns with the change, saying that the single stair may endanger residents despite the provisions requiring sprinklers and extra-wide stairwells so that evacuees can go down while first responders go up. While firefighters were consulted, they feel that their concerns were not adequately addressed and their professional association in BC opposes the changes.

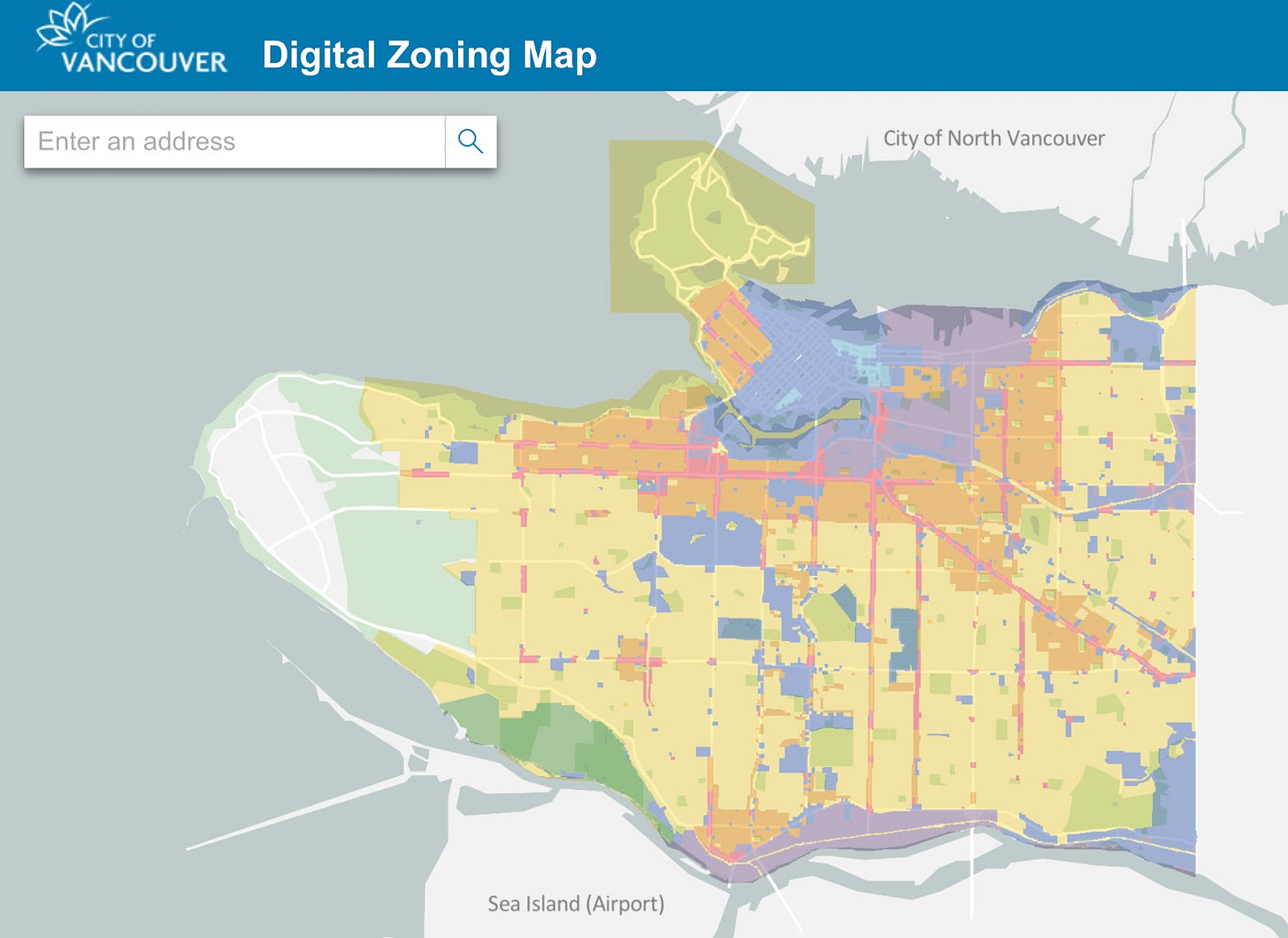

To maximize the effect of the single egress reform, Vancouver and surrounding cities in the lower mainland will need to adopt the change in their municipal requirements and update their zoning laws to allow apartment buildings in more areas of their cities. While Vancouver City Council approved a motion to study the implementation of the single egress law, the Vancouver City Planning Commission, an advisory committee without binding power, unanimously rejected the motion. Vancouver’s current zoning regulations do not allow buildings to exceed three storeys in the yellow and orange areas in the below map.

As the Province eagerly awaits the official results of the BC election – held on October 19th but with a winner still to be determined – the future of BC’s housing laws may hang in the balance. David Eby’s New Democrats introduced the single stair reforms along with other bills aimed at increasing housing supply through intensification, while John Rustad’s Conservatives have pledged to reverse the NDP’s intensification efforts and hope to increase supply by speeding up approvals permitting. As of the time of writing, the NDP hold 46 seats to the Conservative’s 45 with at least two recounts scheduled for October 26th for races where the NDP lead by fewer than 100 votes. As housing prices soar nationwide, BC’s promising single-stair experiment is at risk.

Jacob Kates Rose (he//him) is Deputy Editor of The Bell and a public policy nerd passionate about land use policy, immigration and refugees, and international diplomacy. He has a background in municipal politics and NGO work. He studied in the Department of Peace, Conflict and Justice studies at UofT. Jacob aspires to be wrong often and be right an increasing amount over time. Current podcast recommendation: Good On Paper with Jerusalem Demsas.

Hmmmmm .....

The requirement for two stairways is simply a safety issue in the event of fire. That being so, if one goes to a single stairway for units are there other safety factors that would be required and, if so, would those other requirements lead to increased costs? Alternatively, if there are no additional safety factors, has there been any studies to determine the potential reduction in safety by "x %" due to a single stairway?

Finally, in my jurisdiction, it seems to me that most residential buildings of six or fewer stories are primarily built of wood. Is that the best construction material if single stairways are utilized?