Transcending Boundaries: Indigenous Knowledge in Space Debris Governance

Indigenous voices marginalized in space discussions could find representation through the space debris problem. But, caution is needed to avoid knowledge exploitation.

By Julian Lam

IN THE RUSH TO CLAIM EARTH’S ORBIT, Indigenous voices have been pushed to the margins. Reflecting a trend in space policy, the views of minority groups and non-space faring communities have been repeatedly excluded in discussions about galactic expansion and management of near-earth space. However, an emerging issue in space fora could be the key to unlocking Indigenous voices at the policy table: the space debris problem.

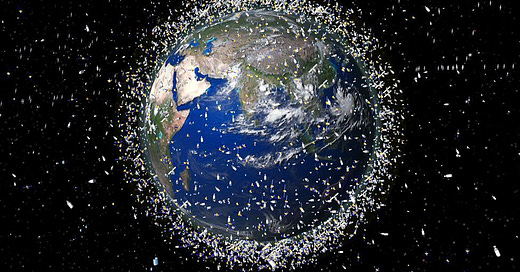

Space debris, also known as space junk, encompasses defunct satellites, spent rocket stages, and other fragments that orbit the Earth. The accumulation of debris has become a pressing concern for space agencies and experts worldwide. These remnants pose risks to operational satellites, manned spacecraft, and even the International Space Station, stressing the need for effective space debris management and mitigation strategies.

Environmental space academics such as professor Moriba Jah have pointed towards principles of “stewardship” and “custodianship” found in Aboriginal communities used to combat climate change as transplantable to governing space debris management – finding a parallel between the climate change crisis and the space debris issue. Yet an underlying caution presents itself with this proposal: the potential exploitation of traditional knowledge systems.

“Picture a pasture open to all. It is to be expected that each herdman will try to keep as many cattle as possible on the commons” – Garrett Hardin

The climate change crisis and space debris problem, together, hinge on a parable known as the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’. These challenges epitomize the delicate balance between individual self-interest and the shared resources that belong to humanity as a whole, creating a fundamental tension that must be addressed. Between rising temperatures and the proliferation of defunct space material, both issues have generated cascading effects on their respective natural and orbital environments at the expense of common human resources.

In both the realms of space and Earth, the role of herdsmen depicted by Hardin (1968) is assumed by major industrial and spacefaring nations, while cattle represents factories and satellites, and the commons symbolize Earth's climate and orbit. From climate change causing rising sea levels globally to fragments of space debris rapidly rising as they collide in near-earth orbit, the sustainability of human activity becomes threatened in the present and for future generations. The parallels are not only at the core of these problems, but extend to their related solutions – how so?

During an interview with the Outer Space Institute (OSI) and Green College UBC on “space environmentalism”, Professor Moriba Jah, suggested that insight could be drawn from Aboriginal communities in their careful observation of local natural systems to govern actions in response to climate change, suggesting that the “principles and tenets of traditional Indigenous ecological knowledge to come back into balance with existence” can be highly applicable in a space domain.

Citing principles of “stewardship” and “custodianship”, Jah and others propose a departure from an elitist and self-interested view of space, to a format where one should care for near earth space as a commons to human kind. By transplanting Indigenous voices into this domain, Jah potentially creates a space for a perspective that has historical and cultural ties to the dark skies.

This ‘transplantation’ is hardly novel, as Indigenous knowledge systems have been employed from fire management in Alaska to wildlife protection in New York State. Appearing to show the ability for these principles to transcend their traditional contexts, an underlying problem exists with this solution: a potential for knowledge exploitation.

According to the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, obtaining access to a community's knowledge resources should be contingent upon obtaining free, prior, and informed consent. However, this requirement is primarily advisory in nature. Already in a precarious state with a lack of established representation in space fora, Indigenous groups are unable to control being subject to knowledge acquisition. Though perhaps not mal-intentioned, Jah never refers to a specific system of knowledge or receiving consent to use the cases he refers to during the interview.

There appears to be a degree of asymmetry; yes, an Indigenous voice is being placed in space fora, and yet there is a lack of acknowledgement or attribution that critically reduces its power. Are there forms of meaningful recourse to guard against exploitation? Unfortunately, the answer is not really. Intellectual property law has been cited for specific cases of traditional knowledge systems in Indigenous climate change solutions, however, this is not codified. Therefore, what should be done about space?

To conclude, Indigenous voices that have been historically marginalized in discussions on space have the potential to provide critical insights into improved management and governance to address the Tragedy of the Commons problem in near earth space. However, the lack of recourse and consensual use of traditional knowledge systems makes transplantation particularly troubling. Therefore, academics and leaders need to realize maintaining its integrity must be at the core of any knowledge transmission – the onus must be on them to maintain the probity of Indigenous voices in space fora.

Julian Lam is a Master of Public Policy candidate at McGill’s Max Bell School of Public Policy as a McCall MacBain scholar. His interests lie at the nexus of international relations, technology and finance.

Really interesting perspective from Julian on this important and swiftly-growing problem of orbital debris. I wonder, however, whether this problem is currently within the reach of any of those policymakers who would be likely to hear Indigenous voices. It is conceivable that more or less pluralistic governments like Canada, US and EU could regulate the Elon Musks and Jeff Bezoses of the world. But what proportion of new space debris is going to come from China, Russia or North Korea and what are the chances those authorities might comply with a more inclusive vision for the near-space environment?