Unlocking Potential: How Regulatory Measures Are Driving Energy Efficiency in France

How can Canada learn from France's regulatory model?

By Zhumin Xu

CLIMATE CHANGE CONTINUES to be one of the most pressing issues of our time. In an effort to combat this global threat, the international community came together and adopted the Paris Agreement at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP21) in 2015. This international treaty on climate change calls for the world to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. In the quest to reshape the future, the limelight turns to energy efficiency, particularly, energy-efficient buildings. This intriguing field serves a dual purpose: combating climate change and improving socio-economic conditions, making it a compelling area for exploration and policy action.

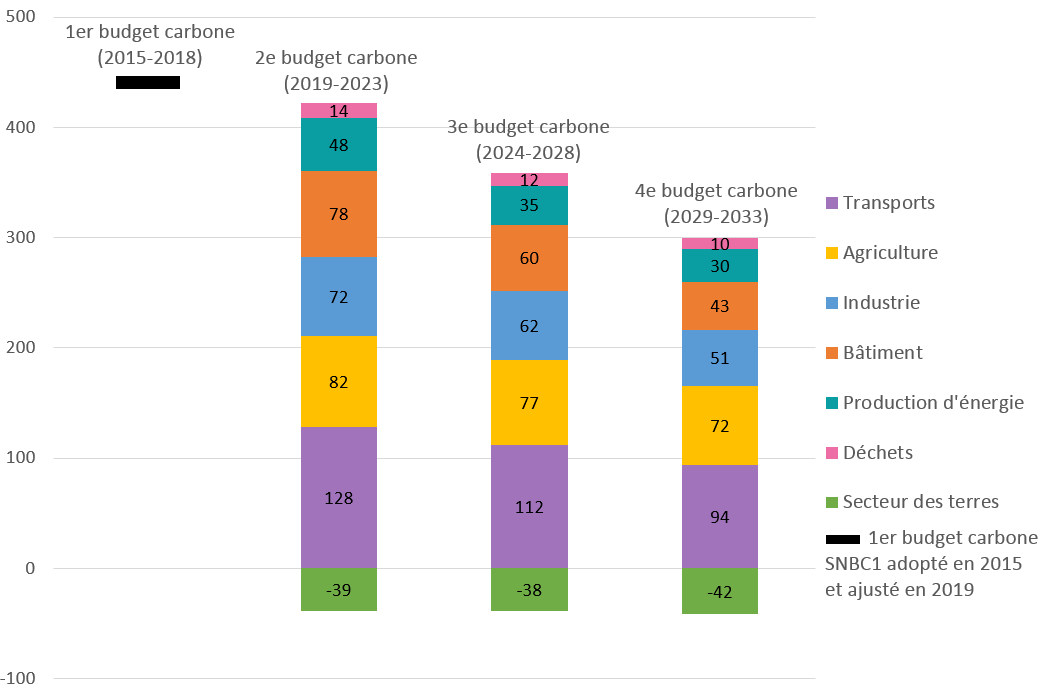

Source: SNBC 2020

In Europe, both economic policies and regulatory tools are being utilized to enhance the viability of renewable energy initiatives among those global pioneers. The goal of these strategies is to ease access to the grid and simplify approval processes, thus enabling a wider spectrum of stakeholders to engage. In 2015, the European Commission launched the new integrated Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy. Those who have signed the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy have pledged to develop and put into action a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP) before the year 2030. A SECAP is designed to establish mitigation strategies that enable a reduction of CO2 emissions by a minimum of 40%. In France specifically, local governments have put forth Le Plan Climat-Air-Énergie Territorial (PCAET) documents. These documents provide a detailed evaluation of the local geographic, demographic, and energy circumstances in their respective regions.

Regulations play a crucial role in unleashing the energy efficiency potential, and Canada could learn from France’s regulatory models. Since 2020, the national low-carbon strategy Stratégie nationale bas carbone (SNBC) in France has explicitly integrated the objective of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050. In order to reach this objective, the SNBC formulates carbon budgets for the periods 2019-2023, 2024-2028, and 2029-2033. These carbon budgets are segmented according to the different sectors of greenhouse gas emissions in France.

Various public policy instruments are currently in place in France to reduce energy consumption and develop renewable energies. Feed-in tariffs exist for renewable energy installations with a capacity of less than 500 kW for photovoltaic systems, or 3 MW or 3 production units for wind energy. Larger installations are subject to market remuneration mechanisms but can receive financial bonuses from the national government or benefit from national project calls.

A significant public policy instrument aimed at boosting energy efficiency in France is the CEE, Certificats d'économies d'énergie (Energy Saving Certificates or White Certificates). It enables the promotion and stimulation of investments in terms of energy efficiency through a market mechanism. This system requires energy suppliers, including electricity, gas, and heating oil, to achieve energy-saving targets by promoting energy efficiency measures among their customers. If the energy suppliers do not meet these targets, they could face substantial penalties.

Under the CEE scheme, energy saving can be achieved in various ways, such as by improving insulation in homes, upgrading heating systems to more energy-efficient models, or implementing energy-saving practices in industries and businesses. Once these energy-saving actions have been validated, they can be translated into "white certificates" which demonstrate that the energy suppliers have met their obligations. These certificates can be traded, providing an additional incentive for energy suppliers to promote energy efficiency. The CEE scheme, therefore, acts as a market-based instrument to stimulate energy efficiency improvements, while also ensuring that energy suppliers play an active role in France's energy transition.

In addition to national efforts, local measures play an integral role in advancing energy efficiency and renewable energy projects in France. For instance, the Paris Region has introduced initiatives such as Calls for Expressions of Interest (AMI, Appel à manifestation d’intérêt) and Calls for Projects (AAP, Appels à projets). These initiatives are aimed at stimulating and funding renewable energy ventures within their jurisdictions.

These funding mechanisms are primarily designed to shoulder the investment costs associated with such projects. They aim to lessen the financial burdens that might otherwise deter individuals, communities, or companies from undertaking renewable energy initiatives. By addressing the financial barriers typically associated with high upfront costs of renewable energy projects, these measures can encourage wider participation in the transition towards a more sustainable energy future.

Source: ecologie.gouv.fr

In France, there’s a mandate requiring homeowners to carry out energy audits and assign building performance ratings by 2025. The recent law for climate and resilience, known as Loi Climat et Résilience, has reinforced these orientations for the housing sector. It establishes progressive regulations that make it illegal to rent out apartments or houses with an F or G energy performance rating in France. Landlords are therefore obligated to renovate these buildings to improve their energy efficiency.

Additionally, the reform of energy performance assessment criteria includes the integration of information on carbon emissions associated with buildings. This broader perspective on building performance acknowledges the importance of reducing carbon emissions throughout the entire lifecycle of a building, including its operation and embodied carbon. Energy audits act as a useful tool for homeowners, enabling them to comprehend their typical energy use and make knowledgeable choices about energy efficiency enhancements in their residences.

In the last quarter of 2022, France’s carbon emissions were successfully curtailed by 8.5 percent, aligning with its national targets but falling short of both the European Union's (EU) objectives and those outlined in the Paris Agreement. The path France has taken provides valuable lessons for Canada as it navigates its own journey towards energy efficiency. The French model demonstrates the pivotal role of regulatory measures in achieving energy efficiency goals. Mandatory energy audits and performance grading of buildings, feed-in tariffs, and the implementation of innovative initiatives like the CEE scheme, all contribute to creating a comprehensive ecosystem that fosters energy efficiency. Despite the established certification mechanisms, it’s crucial to align these incentives with the practical realities of energy markets. Overdependence on such incentives might skew market dynamics, potentially leading to practices that are not sustainable over time.

Admittedly, Canada and France may use different strategies and policy approaches to deal with carbon emissions and energy efficiency due to the factors including their energy sources, industrial composition and weather patterns. Regulations create a legal obligation for entities to comply with emission reduction targets and guidelines. The imposition of punitive measures for non-compliance, such as fines and sanctions, serves to provide a powerful incentive for governments and organizations alike to initiate and implement effective actions. This approach ensures the seriousness of carbon reduction goals in Canada and strengthens the resolve to achieve a more sustainable and cleaner future.

Zhumin Xu is a research assistant at the School of Social Work at McGill. In 2022, Zhumin founded the City Culture Lab, an NGO based in the Paris Metropolitan Area, and has presented her research at more than 20 conferences across five continents, spanning eight different countries. Zhumin has also served as a Guest Lecturer at the University of Hong Kong, University of New Orleans, and East China University of Science and Technology.

Of course, reducing energy demand is much less critical where energy sources are minimal-emitting. This is true of the hydro and nuclear that displaced coal from France's grid decades ago. If a jurisdiction begins to favour wind and solar over nuclear, as in Germany, paradoxically this drives greater demand for gas-fired generating plants to back up the wind and solar, so emissions don't fall.