What will it take to keep democracy as the standard for global governance?

As China and Russia only believe “might makes right,” Western policymakers should respond in the same spirit that these nations have treated the international liberal order.

Pangying Peng is a former Taiwanese diplomat currently pursuing the MPP at the Max Bell School of Public Policy, McGill University. This article reflects only his personal views. A slightly shorter version of this article has been published on It Was Always Burning of the School of Public and International Affairs, Columbia University.

Write us at newsletterthebell@gmail.com.

IN 1992, THE AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENTIST Francis Fukuyama heralded democracy as the endpoint of human ideological evolution and the final form of governance. The end of the Cold War rendered the West too complacent in its conviction that democracy would remain the incontrovertible default standard for global governance.

Reality paints a far bleaker picture 30 years onward from the collapse of the Soviet Union. Over the past two decades, China and Russia have exploited the liberal international order to rise from the wreckage of centrally planned economies. Regardless, they have reinforced their vice-like grip on domestic politics while seeking to destabilize the current international order underpinned by democracy. Worryingly, they have become more nimble and technologically savvy in asserting and exporting social control, gradually swaying the global perception about their model. If we wish to reverse the backsliding of global democracy, we must realign our policies to contend with the rise of authoritarianism.

Strangle democracy with democracy

Autocrats’ intent to subvert democracy often has ideological roots. In China, the prevailing Marxist-Leninist doctrine inevitably leads to its power struggle with Western democracies. Recently, Xi Jinping has repeatedly instructed his party cadres to “wage a determined struggle against the international forces that deter China’s national rejuvenation.” In Russia, Vladimir Putin has dreaded the eastward expansion of democracy to Russia’s border more than that of NATO, as it might inspire democratic movements against his extended presidency. These ideological determinants fuel autocrats’ offensive responses to democracies.

Autocrats learn that the most potent offensive is to weaponize democracy’s institutional “good.” The freedom and openness characteristic of democracies ironically provides opportunities for autocrats to easily infiltrate such a system, and poison it with the system’s own values. For example, they exploit our free press by “deploying” their mouthpieces in our media ecosystem, which misleads us to unfairly scrutinize our governments. To be clear, constructive criticism is fundamental to democracy, but our public discourse has been poisoned by their disinformation. China and Russia excel in identifying the sensitivities in our societies. They study our points of contention and tailor strategies accordingly to stoke unrest. Racial issues are sensitive in America, so they see opportunities to interfere and foment protests. They argue plausibly that China’s treatment of Uyghurs is excusable considering Canada’s policies towards its indigenous people. We believe in free markets, and their state-owned enterprises then enter these markets to undercut our own companies. Autocrats have in many ways evolved - they are no longer archaic North Korean-esque regimes adopting only absurd rhetoric in their propaganda. Many have now become masters of democracy. They have learned to strangle democracy with democracy.

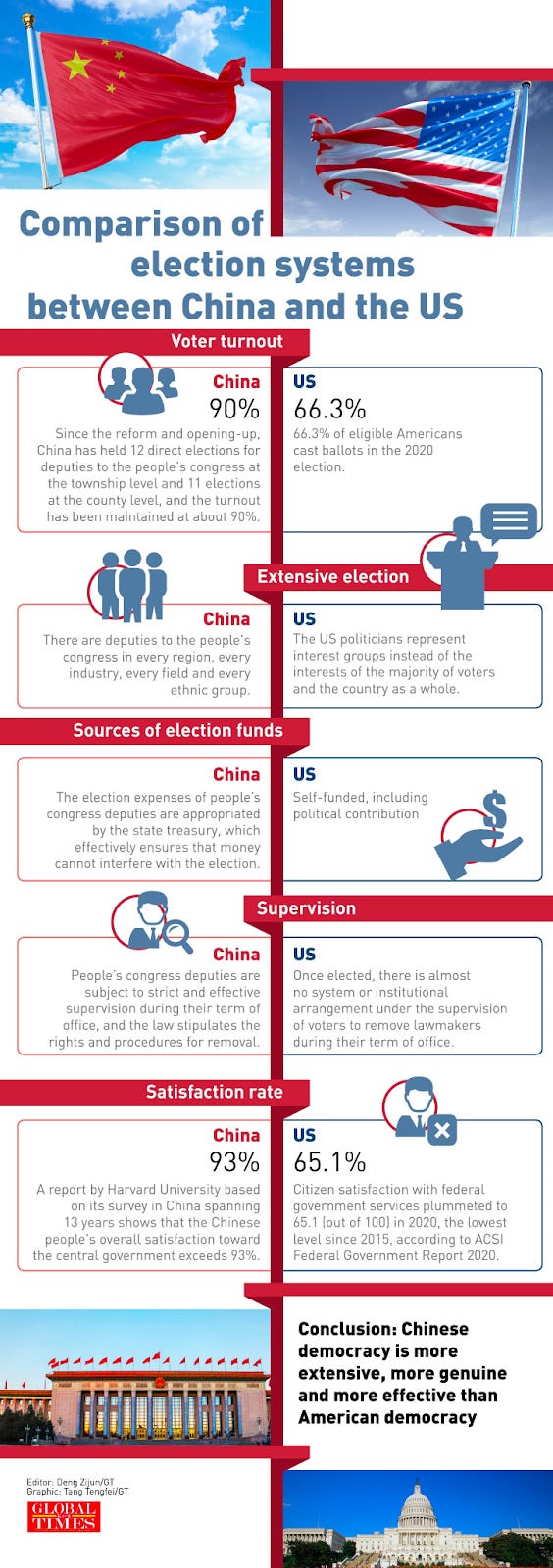

At the global level, autocrats are now more convinced than ever that they are the majority. The share of the global population living in democracies has fallen below 50% this year. Only about 20% now live in fully free countries. Nowadays, by rallying a voting alliance, China has been able to portray Western human rights standards as “minoritarian views” and co-opt the UN Human Rights Council (UNHCR). While 22 countries signed a letter to the UNHCR urging China to end its atrocities against the Uyghurs, 37 countries lauded China’s “anti-terrorist” measures. The Chinese Foreign Ministry publicly argued that the aggregate population of the West counts far less than China, and thus its voice cannot reflect the greater international public opinion. This ironically sounds like autocrats are defending a twisted form of democracy now. As autocrats subtly push their narrative, they also entice countries where democracy is less resilient to change course. Most interestingly, China has begun redefining democracy and portraying its model as an improved version.

Useful idiots & institutional arbitrageurs

Two kinds of people among us are engaging with autocrats at the expense of our democracy.

The first is “useful idiots,” who naïvely believe economic engagement with China and Russia entails no political attachment. They buy the autocrats’ rhetoric that the world is a diverse place and the West should not “impose” its democratic agenda worldwide. The statement is ostensibly impartial, but it helps obfuscate the truth that autocrats repress the freedom and equality their people aspire to. Useful idiots like disputing the criticisms against autocrats by implicating the U.S. However, the distinction is that autocrats do not face institutional checks and balances domestically. Also, they are usually egalitarians, but they ignore that both China and Russia are now two of the most unequal countries in the world. Some with high publicity even maintained that Muslims are treated better in China and Russia than in the U.S. despite ironclad evidence of genocide against Uyghurs based on their “criminality” of simply wearing headscarves and avoiding alcohol.

The second is “institutional arbitrageurs,” who sniff economic profits in the institutional difference between democracy and autocracy. They see opportunities in the Chinese government’s need to have someone put a positive spin for itself in the global media ecosystem. While knowing China deprives its citizens of the right to free speech, institutional arbitrageurs use this freedom guaranteed under Western democracy to propagandize for China on social media and generate fortunes. Their actions leave autocrats with the impression that they can buy off anyone in democracies.

Autocrats don’t play fairly

The crux that the West faces in its engagement with China and Russia can boil down to an unlevel playing field. In the past, we believed that by granting them preferential treatment in the liberal international order, we could spur their economic and political opening, and they would eventually become responsible global stakeholders. However, apart from making ourselves economically dependent on them and weakening our resolve to take countermeasures when they breach international law, we have achieved little.

Canada’s democracy faced a real test when its “two Michaels” were held hostage by China. During the diplomatic crisis, several high-profile Canadian policy practitioners signed a letter calling on Prime Minister Trudeau to intervene in the judiciary to release the Huawei CFO in exchange for Michaels. This is how autocrats push us to relinquish our principles. They now enter our borders to test how robust our democracies really are.

Conversely, the values that the West champions can hardly reach the Chinese population due to its Great Firewall. While it is illegal for Chinese citizens to access Western social media, Chinese diplomats are free to flood Twitter to berate their “Western foes.” While Chinese tech giants can assert First Amendment rights in American courts and potentially share their data with the Chinese government, Google, Facebook and Twitter remain blocked from China. Even in diplomatic relations, while the Chinese ambassador to Canada can use Canada’s free media to threaten Canadians, the Canadian ambassador cannot freely speak of or publish his opinions defending Canada’s policies on Chinese media platforms.

Giving autocrats a taste of their own medicine

Autocracies like China and Russia do not hold all the cards. The leadership of these nations are inherently insecure and feel compelled to wage a global struggle with the West in order to survive. That insecurity is precisely what the West could use to respond to them effectively.

In autocracies, many political elites do not believe their systems are sustainable either. China’s domestic security budget has outweighed its defense expenditure. Chinese and Russian elites have been busy transferring their families and assets to the same Western democracies they portray as evil and imperialist. That evinces why sanctions and entry bans often are their Achilles heel. During the U.S.-China Alaska meeting in 2021, China demanded that America reverse visa restrictions on party members, Chinese students and state-media journalists. In Russia, Putin needs oligarchs’ support to remain in power, so making oligarchs vulnerable through sanctions also made Putin vulnerable.

As China and Russia only believe “might makes right,” Western policymakers should respond in the same spirit that these nations have treated the liberal international order. These responses could include: restricting their mouthpieces in our media ecosystem; banning our banks from housing autocrats’ money; launching cyber operations to dismantle their internet control so that their citizens can assess our perspectives; diversifying our supply chains with more trustworthy partners; and finally, increasing military capabilities to deter autocrats. We must also dismiss our hypocrisy and selective approaches to human rights issues and act consistently. To win more allies in the developing world, the West should release more COVID-19 vaccines at an affordable cost or for free, treat all refugees with the same standards, and help finance poorer countries’ plans to transition away from fossil fuels to adapt to a warming world.

Perhaps democracy as a governance model has truly become a minority model associated with Western traditions only. The question remains: are we prepared to accept that reality, or double down on our efforts to make democracy the preeminent standard for global governance?

The Bell is edited by Jaclyn Victor, Jason Kreutz, Shweta Menon and Phaedra de Saint-Rome of the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University.